jueves, 27 de febrero de 2020

Maíz Bofo

Se caracteriza por sus mazorcas alargadas y semi elípticas con granos multicolor. Es considerado el maíz sagrado de los pueblos Wixárika (Huichol).

Via: @_SemillasdeVida miércoles, 26 de febrero de 2020

.

Finally out of reach-

No bondage, no dependency.

How calm the ocean,

Towering the void.

.

.

Tessho

.

domingo, 23 de febrero de 2020

On the predictability of infectious disease outbreaks

Scarpino and Petri, 2019.

Scarpino and Petri, 2019.

Infectious disease outbreaks recapitulate biology: they emerge from the

multi-level interaction of hosts, pathogens, and environment. Therefore,

outbreak forecasting requires an integrative approach to modeling.

While specific components of outbreaks are predictable, it remains

unclear whether fundamental limits to outbreak prediction exist. Here,

adopting permutation entropy as a model independent measure of

predictability, we study the predictability of a diverse collection of

outbreaks and identify a fundamental entropy barrier for disease time

series forecasting. However, this barrier is often beyond the time scale

of single outbreaks, implying prediction is likely to succeed. We show

that forecast horizons vary by disease and that both shifting model

structures and social network heterogeneity are likely mechanisms for

differences in predictability. Our results highlight the importance of

embracing dynamic modeling approaches, suggest challenges for performing

model selection across long time series, and may relate more broadly to

the predictability of complex adaptive systems.

Single outbreaks are often predictable. a The average predictability (1 − Hp)

for weekly, state-level data from nine diseases is plotted as a

function of time-series length in weeks. For each disease, we selected

1000 random starting locations in each time series and calculated the

permutation entropy in rolling windows in lengths ranging from 2 to 104

weeks. The solid lines indicate the mean value and the shaded region

marks the interquartile range across all states and starting locations

in the time series. Although the slopes are different for each disease,

in all cases, longer time series result in lower predictability.

However, most diseases are predictable across single outbreaks and

disease time series cluster together, i.e. there are disease-specific

slopes on the relationship between predictability and time-series

length. To aid in interpretation, the black dashed line plots the median

permutation entropy across 20,000 stochastic simulations of a

Susceptible Infectious Recovered (SIR) model, as described in the

Supplement. This SIR model would be considered predictable, thus values

above the black line might be thought of as in-the-range where

model-based forecasts are expected to outperform forecasts based solely

on statistical properties of the time-series data. The dark brown,

dashed vertical line indicates the time period selected for b. In b,

the predictability is shown after 4 months, i.e. 16 weeks, of data for

each pathogen. The same procedure was used to generate the permutation

entropy as in a. The mean predictability differed both by disease

and by geographic location, i.e state (analysis of variance with post

hoc Tukey honest significant differences test and correction for

multiple comparison, sum of squares (SS) disease = 98.22, degrees of

freedom (DF) disease = 8, p-value disease < 0.001; SS location = 94.7, DF location = 53, p-value

location < 0.001). The solid line represents the median, boxes

enclose the 25th to 75th percentiles of the distributions, and whiskers

cover the entire distribution

jueves, 20 de febrero de 2020

miércoles, 19 de febrero de 2020

Towards an integrative understanding of soil biodiversity

Thakur et al., 2019

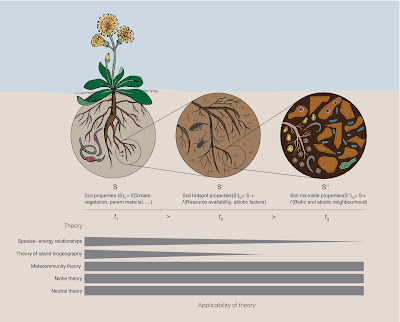

Soil is one of the most biodiverse terrestrial habitats. Yet, we lack an integrative conceptual framework for understanding the patterns and mechanisms driving soil biodiversity. One of the underlying reasons for our poor understanding of soil biodiversity patterns relates to whether key biodiversity theories (historically developed for aboveground and aquatic organisms) are applicable to patterns of soil biodiversity. Here, we present a systematic literature review to investigate whether and how key biodiversity theories (species–energy relationship, theory of island biogeography, metacommunity theory, niche theory and neutral theory) can explain observed patterns of soil biodiversity. We then discuss two spatial compartments nested within soil at which biodiversity theories can be applied to acknowledge the scale‐dependent nature of soil biodiversity.

Illustration of spatial compartments in the soil for studying soil biodiversity from micro‐ to macroorganisms. The properties of each compartment that potentially affect the respective biodiversity pattern are listed below the compartments. As we begin to zoom in from soil (S) to soil microsites (S″), the applicability of some biodiversity theories may also change (indicated by thickness of grey bars below the figure). Soil micro‐aggregates are coloured light brown in the S″ compartment; all organisms in S″ are either microorganisms or their predators (e.g. nematodes and protists). Note that microorganisms also can colonize micro‐aggregates as illustrated in S″. Since the temporal scale (t) also co‐varies with spatial scale (Wolkovich et al., 2014), the figure presents three different temporal scales (t1–t3) corresponding to the three spatial scales. f, function.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/brv.12567

.

Thakur et al., 2019

Soil is one of the most biodiverse terrestrial habitats. Yet, we lack an integrative conceptual framework for understanding the patterns and mechanisms driving soil biodiversity. One of the underlying reasons for our poor understanding of soil biodiversity patterns relates to whether key biodiversity theories (historically developed for aboveground and aquatic organisms) are applicable to patterns of soil biodiversity. Here, we present a systematic literature review to investigate whether and how key biodiversity theories (species–energy relationship, theory of island biogeography, metacommunity theory, niche theory and neutral theory) can explain observed patterns of soil biodiversity. We then discuss two spatial compartments nested within soil at which biodiversity theories can be applied to acknowledge the scale‐dependent nature of soil biodiversity.

Illustration of spatial compartments in the soil for studying soil biodiversity from micro‐ to macroorganisms. The properties of each compartment that potentially affect the respective biodiversity pattern are listed below the compartments. As we begin to zoom in from soil (S) to soil microsites (S″), the applicability of some biodiversity theories may also change (indicated by thickness of grey bars below the figure). Soil micro‐aggregates are coloured light brown in the S″ compartment; all organisms in S″ are either microorganisms or their predators (e.g. nematodes and protists). Note that microorganisms also can colonize micro‐aggregates as illustrated in S″. Since the temporal scale (t) also co‐varies with spatial scale (Wolkovich et al., 2014), the figure presents three different temporal scales (t1–t3) corresponding to the three spatial scales. f, function.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/brv.12567

.

lunes, 17 de febrero de 2020

Para

identificar a los productores y asegurar la calidad del pan, los panaderos de

finales del siglo XVIII de la ciudad de Caracas proponen colocar marcas a su

producción. Aquí algunas de esas marcas o señales (1787).

Fondo Archivo General de la Nación, sub-fondo “Colonia”, Sección Política y

Gobierno”, serie “Gobernación y Capitanía General”, Tomo XXXI, Folios 1 a 24.

Fuente: @HistoriaPapeles

.

domingo, 16 de febrero de 2020

Insights into the assembly rules of a continent-wide multilayer network

Mello et al, 2019.

Mello et al, 2019.

How are ecological systems assembled? Identifying common structural

patterns within complex networks of interacting species has been a major

challenge in ecology, but researchers have focused primarily on single

interaction types aggregating in space or time. Here, we shed light on

the assembly rules of a multilayer network formed by frugivory and

nectarivory interactions between bats and plants in the Neotropics. By

harnessing a conceptual framework known as the integrative hypothesis of

specialization, our results suggest that phylogenetic constraints

separate species into different layers and shape the network’s modules.

Then, the network shifts to a nested structure within its modules where

interactions are mainly structured by geographic co-occurrence. Finally,

organismal traits related to consuming fruits or nectar determine which

bat species are central or peripheral to the network. Our results

provide insights into how different processes contribute to the

assemblage of ecological systems at different levels of organization,

resulting in a compound network topology.

The bat–plant multilayer network. By compiling bat–plant interactions

(lines) across the Neotropics, we found a compound topology with a

strong separation between interaction types (layers) and guilds

(modules). The layers represent interactions of frugivory, nectarivory

and dual interactions. Modules were detected using the LPA.

.

jueves, 13 de febrero de 2020

Increasing crop heterogeneity enhances multitrophic diversity across agricultural regions

Sirami et al., 2019

Agricultural landscape homogenization is a major ongoing threat to

biodiversity and the delivery of key ecosystem services for human

well-being. It is well known that increasing the amount of seminatural

cover in agricultural landscapes has a positive effect on biodiversity.

However, little is known about the role of the crop mosaic itself. Crop

heterogeneity in the landscape had a much stronger effect on

multitrophic diversity than the amount of seminatural cover in the

landscape, across 435 agricultural landscapes located in 8 European and

North American regions. Increasing crop heterogeneity can be an

effective way to mitigate the impacts of farming on biodiversity without

taking land out of production.

Agricultural landscape homogenization has detrimental effects on

biodiversity and key ecosystem services. Increasing agricultural

landscape heterogeneity by increasing seminatural cover can help to

mitigate biodiversity loss. However, the amount of seminatural cover is

generally low and difficult to increase in many intensively managed

agricultural landscapes. We hypothesized that increasing the

heterogeneity of the crop mosaic itself (hereafter “crop heterogeneity”)

can also have positive effects on biodiversity. In 8 contrasting

regions of Europe and North America, we selected 435 landscapes along

independent gradients of crop diversity and mean field size. Within each

landscape, we selected 3 sampling sites in 1, 2, or 3 crop types. We

sampled 7 taxa (plants, bees, butterflies, hoverflies, carabids,

spiders, and birds) and calculated a synthetic index of multitrophic

diversity at the landscape level. Increasing crop heterogeneity was more

beneficial for multitrophic diversity than increasing seminatural

cover. For instance, the effect of decreasing mean field size from 5 to

2.8 ha was as strong as the effect of increasing seminatural cover from

0.5 to 11%. Decreasing mean field size benefited multitrophic diversity

even in the absence of seminatural vegetation between fields. Increasing

the number of crop types sampled had a positive effect on

landscape-level multitrophic diversity. However, the effect of

increasing crop diversity in the landscape surrounding fields sampled

depended on the amount of seminatural cover. Our study provides

large-scale, multitrophic, cross-regional evidence that increasing crop

heterogeneity can be an effective way to increase biodiversity in

agricultural landscapes without taking land out of agricultural

production.

(A) Traditional and (B) alternative representations of

agricultural landscape heterogeneity, focusing either on seminatural

heterogeneity or crop heterogeneity, are associated with distinct

hypotheses.

.

martes, 11 de febrero de 2020

Ecological changes with minor effect initiate evolution to delayed regime shifts

P. Catalina Chaparro-Pedraza and André M. de Roos, 2010.

Regime shifts have been documented in a variety of natural and social

systems. These abrupt transitions produce dramatic shifts in the

composition and functioning of socioecological systems. Existing theory

on ecosystem resilience has only considered regime shifts to be caused

by changes in external conditions beyond a tipping point and therefore

lacks an evolutionary perspective. In this study, we show how a change

in external conditions has little ecological effect and does not push

the system beyond a tipping point. The change therefore does not cause

an immediate regime shift but instead triggers an evolutionary process

that drives a phenotypic trait beyond a tipping point, thereby resulting

(after a substantial delay) in a selection-induced regime shift. Our

finding draws attention to the fact that regime shifts observed in the

present may result from changes in the distant past, and highlights the

need for integrating evolutionary dynamics into the theoretical

foundation for ecosystem resilience.

.

lunes, 10 de febrero de 2020

.

What's travel and what good is it? We never disembark from ourselves.

The true landscapes are those that we ourselves create. I've crossed more seas than anyone. I've seen more mountains than there are on earth.

The universe isn't mine: it's me.

Fernando Pessoa

.

What's travel and what good is it? We never disembark from ourselves.

The true landscapes are those that we ourselves create. I've crossed more seas than anyone. I've seen more mountains than there are on earth.

The universe isn't mine: it's me.

Fernando Pessoa

.

domingo, 9 de febrero de 2020

Soil fungal assemblage complexity is dependent on soil fertility and dominated by deterministic processes

Junjie Guo et al., 2020

- In the processes controlling ecosystem fertility, fungi are increasingly acknowledged as key drivers. However, our understanding of the rules behind fungal community assembly regarding the effect of soil fertility level remains limited.

- Using soil samples from typical tea plantations spanning c. 2167 km north‐east to south‐west across China, we investigated the assemblage complexity and assembly processes of 140 fungal communities along a soil fertility gradient.

- The community dissimilarities of total fungi and fungal functional guilds increased with increasing soil fertility index dissimilarity. The symbiotrophs were more sensitive to variations in soil fertility compared with pathotrophs and saprotrophs. Fungal networks were larger and showed higher connectivity as well as greater potential for inter‐module connection in more fertile soils. Environmental factors had a slightly greater influence on fungal community composition than spatial factors. Species abundance fitted the Zipf–Mandelbrot distribution (niche‐based mechanisms), which provided evidence for deterministic‐based processes.

- Overall, the soil fungal communities in tea plantations responded in a deterministic manner to soil fertility, with high fertility correlated with complex fungal community assemblages. This study provides new insights that might contribute to predictions of fungal community complexity.

Bruno Latour - Gaia 2.0/Down to Earth

miércoles, 5 de febrero de 2020

.

Suppose we did out work

like the snow, quietly, quietly,

leaving nothing out.

Wendell Berry

.

Suppose we did out work

like the snow, quietly, quietly,

leaving nothing out.

Wendell Berry

.

martes, 4 de febrero de 2020

A social–ecological analysis of the global agrifood system

Oteros-Rozas et al., 2019.

Oteros-Rozas et al., 2019.

Eradicating world hunger—the aim of Sustainable Development Goal 2

(SDG2)—requires a social–ecological approach to agrifood systems.

However, previous work has mostly focused on one or the other. Here, we

apply such a holistic approach to depicting the global food panorama

through a quantitative multivariate assessment of 43 indicators of food

sovereignty and 28 indicators of sociodemographics, social being, and

environmental sustainability in 150 countries. The results identify 5

world regions and indicate the existence of an agrifood debt (i.e.,

disequilibria between regions in the natural resources consumed, the

environmental impacts produced, and the social wellbeing attained by

populations that play different roles within the globalized agrifood

system). Three spotlights underpin this debt: 1) a severe contrast in

diets and food security between regions, 2) a concern about the role

that international agrifood trade is playing in regional food security,

and 3) a mismatch between regional biocapacity and food security. Our

results contribute to broadening the debate beyond food security from a

social–ecological perspective, incorporating environmental and social

dimensions.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)